Optimism Bias

What is it?

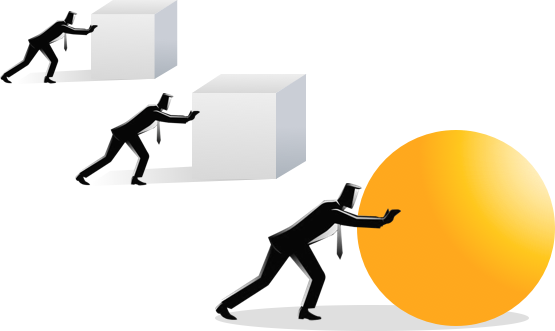

When we overestimate the odds of our own success compared to other's.

Example:

In the Western world, divorce rates are about 40%. sk a newlywed about the odds of eventual divorce, they'll say 0%. Even divorce lawyers underestimate the number